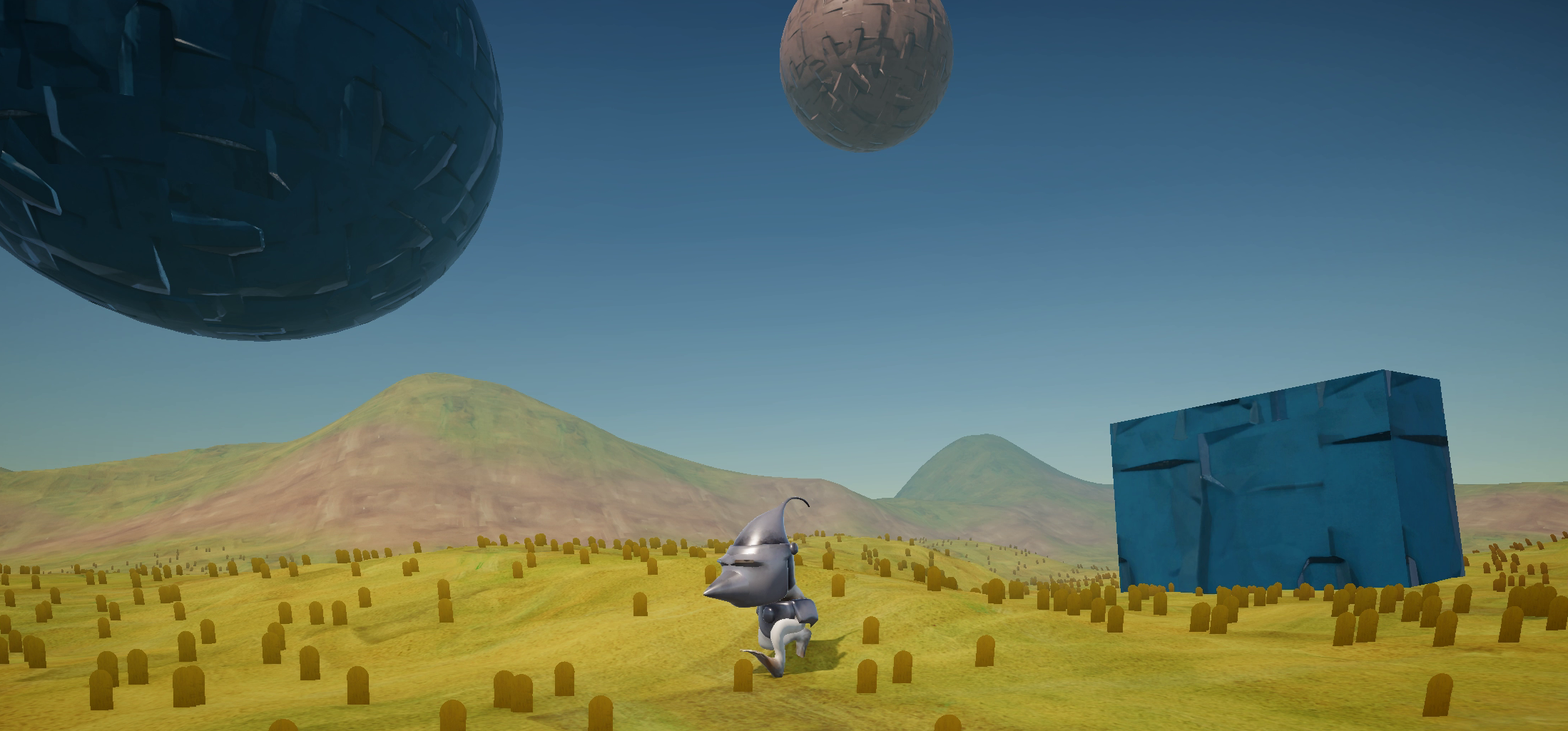

Authoritative Multiplayer Demo [2025]

Github page

This project is a fully authoritative and deterministic 3D platformer built using Unity’s low-level networking library, Unity Transport.

It implements many foundational multiplayer features, including:

- Client-side prediction

- Input buffering

- Guaranteed and non-guaranteed message delivery

- Data quantization and compression for bandwidth efficiency

At its core, the architecture is driven by a set of services, each with a Tick() method. Both the server and client call Tick() on a fixed interval (e.g., 20 Hz for server logic, 60 Hz for client-side prediction), ensuring synchronized and deterministic simulation.

Much of this system was inspired by the classic paper, “The TRIBES Engine Networking Model”. The game came out in 1998 but I was blown away by how performant and data efficient it was to support 128 players at the time of dial-up connections which is a true testament to its design. Link to the paper

Connection Manager

Both the client and server use a ConnectionManager to check for incoming data, which may include player state updates, events, or new player connections.

When a packet is received, the ConnectionManager reads its ID and forwards it to the appropriate system for processing.

private void processPacketID(byte id, DataStreamReader stream)

{

switch (id)

{

case GamePackets.HELLO_ID:

playerID = stream.ReadUInt();

if (movementManager.playerDict.ContainsKey(playerID))

{

var head = movementManager.playerDict[playerID].head;

Camera.main.GetComponent<PlayerCamera>().SetFollowTransform(head); //Make the camera follow us

}

Debug.Log($"{playerID} is our new id!");

break;

case GamePackets.MOV_MANAGER_ID:

movementManager.ProcessPlayerStatePacket(stream);

break;

case GamePackets.EVENT_MANAGER_ID:

eventManager.ProcessEventsPacket(stream);

break;

}

}

In addition to routing packets, the ConnectionManager is responsible for setting up Unity Transport pipelines for both guaranteed (reliable) and non-guaranteed (unreliable) messages. This separation helps optimize performance by using the right delivery mode for each type of data.

Movement Manager

Client-Side:

The client is responsible for sending a new input every tick. These input packets are sent unreliably to reduce latency, since unreliable messages are faster and more efficient for high-frequency data. Since the client only sends inputs to the server it makes it a lot harder to cheat. This is what makes it an authoritative server. The client has no control over it’s final state.

Each input is tagged with a unique ID to ensure correct ordering. The client expects to eventually receive a matching state ID from the server that corresponds to the inputs it sent. However, since the network is unreliable and packets may be lost, the client doesn’t just send the input from the current tick. Instead, the MovementManager resends all unacknowledged inputs until they are confirmed by the server:

//Add to input list

inputList.Add(new Player.PlayerInput(moveValue, jumpAction.IsPressed(), Camera.main.transform.rotation.eulerAngles.y, tickCounter));

writer.WriteByte(GamePackets.INPUT_ID); //Packet Id

//Write every input in our queue

for (int i = inputList.Count - 1; i > Mathf.Max(0, inputList.Count - TickConfig.INPUT_MAX - 1); i--)

{

Player.PlayerInput input = inputList[i];

byte moveFlags = GetMoveByte(input);

writer.WriteByte(moveFlags); //move data

writer.WriteFloat(input.camY); //cam rot

writer.WriteUInt(input.id); //Tick ID

}

connectionManager.networkDriver.EndSend(writer);

Client-Side Prediction

The client also simulates the latest input locally. Because the simulation is deterministic, the result will usually match what the server eventually sends back.

if (playerDict.ContainsKey(connectionManager.playerID)) //simulate player packet

{

playerDict[connectionManager.playerID].MovePlayer(moveValue, jumpAction.IsPressed(), Camera.main.transform.rotation.eulerAngles.y);

}

This technique is called client-side prediction and makes the game feel responsive despite network delay.

Reconciliation

Sometimes the client’s prediction will differ from the server’s authoritative state. When this happens, the client performs reconciliation. First, it resets the local player to the state received from the server. However, that state is a few ticks old. To catch up, the client replays every input it has made since that state:

//Replay all inputs since last acknowledged state

for (int i = 0; i < inputList.Count; i++)

{

MovePlayer(inputList[i].moveValue, inputList[i].jump, inputList[i].camY);

KinematicCharacterSystem.Simulate(TickConfig.CLIENT_TICK_TIME, new List<KinematicCharacterMotor>{motor}, new List<PhysicsMover>());

}

This correction may cause the player to appear to teleport slightly, which can feel jarring. This visual artifact is usually smoothed out later with interpolation or smoothing algorithms.

Server Side:

The server is responsible for reading client inputs and, once per tick, sending back an authoritative state update for each player. Because packets may occasionally be lost in transit, the server keeps a buffer of the last two ticks of inputs for each client. Since clients resend all unacknowledged inputs every tick, the server uses this buffer to ensure it has the correct inputs before simulating a movement tick.

In rare cases—typically under high packet loss conditions (5% or more)—the server may still not receive the expected input for a given tick. In that case, it reuses the most recent available input:

GamePackets.MoveInput data;

if (!playerBuffer.TryGetValue(expectedInputID, out data))

{

//We don't have the packet we expect so use whatever was last

Debug.Log($"{playerID} Missing packet {expectedInputID}");

playerBuffer[expectedInputID] = playerBuffer[expectedInputID - 1];

data = playerBuffer[expectedInputID];

}

This fallback strategy works well because players typically don’t change their inputs every single frame. Reusing the last input often results in a close approximation of the intended action, and the client can still reconcile the correct result later through resimulation.

Interpolation:

Interpolation is needed for two reasons.

- Client-side prediction corrections — When the prediction is wrong, snapping to the server-corrected position would be visually jarring.

- Smoothing the movement of other players — Since the client doesn’t simulate other players locally, we rely entirely on state packets from the server. If one is dropped, their position can jump noticeably without smoothing.

To solve this, I implemented a simple dampening system that gradually moves the visible player model toward the actual simulated position. If the difference becomes too large, we snap the model instantly—though this rarely happens in practice.

transform.rotation = followTrans.rotation;

Vector3 delta = followTrans.position - transform.position;

if (delta.magnitude > 3.0f)

{

transform.position = followTrans.position;

Debug.Log("TELEPORT BODY");

}

else

{

float rate = Mathf.Max(dampenSpeed, delta.magnitude * dampenSpeed);

transform.position += delta * rate * Time.fixedDeltaTime;

}

I initially experimented with linear interpolation (Vector3.Lerp) but found that it introduced noticeable jitter. This dampening approach gave me a smoother and more stable result, especially when packets are delayed or dropped.

What was it all for?

Here’s a video showing a client running under extreme network conditions:

- 500ms round trip time

- 84ms of jitter

- 5% packet loss

The grey sphere trailing behind the player represents the most recent authoritative state received from the server. Despite the heavy latency and loss, the game feels buttery smooth to play! After the session, I checked the logs and confirmed there wasn’t a single missing input packet thanks to redundancy and the buffering system.

Observing Other Players Under the Same Conditions

Multiplayer games also need to render other players accurately under poor network conditions. Here’s a second video showing how remote players look under identical packet loss, jitter, and latency:

While not as smooth as the local player (who benefits from client-side prediction), the results are surprisingly decent given the circumstances. Interpolation and dampening techniques help hide some of the packet delay and jitter.

Event Manager

The Event Manager handles Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs). These are one-off, guaranteed events that must be simulated on both the server and the client. Typical examples include spawning effects, triggering animations, or playing sounds. RPCs are tied to a simple ID-function mapping. On both the server and the client, a dictionary maps each event ID to a corresponding function:

RPCTable = new Dictionary<byte, RPCDelegate>();

Any function can register itself with the Event Manager. When a packet is received, the Event Manager simply looks up the event ID and invokes the linked function. This ensures reliable, deterministic execution of important one-time events. If the event modifies the world in a way that affects player state (e.g., position, velocity, grounded status), those changes are reflected in the state packets sent by the Movement Manager. This maintains authority and consistency without needing to send redundant data.

Future Plans

I’m planning to explore additional interpolation strategies such as:

- Bicubic interpolation for smoother transitions between player states

- Extrapolation to handle longer gaps between incoming state packets

Data Optimization

Currently, some server-sent data is quantized to reduce bandwidth usage. For example, the duration a player holds the jump button is originally a float, but it’s compressed into a byte, reducing its size to a quarter.

In the future I would like to:

- Quantize more player state variables (e.g., velocity or rotation) to use short instead of float. The visual and gameplay impact should be negligible, while significantly reducing bandwidth per player.

- Switch input IDs from unsigned integers to bytes or shorts, with wraparound behavior once the maximum value is reached. This would further reduce packet sizes with minimal complexity.

Instead of representing inputIDs with unsigned integers I want to try using a short or byte that wraps around onces it reaches the max size.

Because both input and state packets are already extremely compact, this system is designed for scalability. I’m aiming to support 100+ concurrent players as this demo evolves into a full-featured game.